Exhibitions

ABOUT THE EXHIBITION

Expanding the scope of the 20th Onion City Experimental Film and Video Festival, the exhibition Focus Pull: Onion City Off Screen is a collaborative effort that includes works in collage, film installation, and single-channel video by Jon Jost, Ken Jacobs, Nicky Hamlyn, Jorge Lorenzo, and Lewis Klahr. Drawing attention to other creative outlets by artists in the experimental film and video community, this exhibition demonstrates that the long tradition of the cross-medium investigation by avant-garde filmmakers is still going strong and, indeed, growing. All the works in Focus Pull display a subtle simplicity that benefits from a form of viewing distinctly unlike that of the traditional movie theater.

Jon Jost is an American independent filmmaker and a good example of an auteur, a director who exerts complete creative control over his films. Deeply rooted in Americana, Jost’s films operate as psychological studies that seem both experientially ingrained but also culturally endemic, encapsulating a sense of profound alienation. Rosenbaum considers Last Chants for a Slow Dance to be Jost’s best film – and also his most disturbing – a portrait of a killer devoid of conscience or reason. At Play in the Fields of the Lord [NEBRASKA], Jost ’s single-channel video projection is, according to the artist, “A meditation piece, an homage to the American plains and the Omaha tribe of Nebraska. It was made while living in Lincoln, Nebraska, and working on a project in the Nebraska Sandhills, around Valentine.”

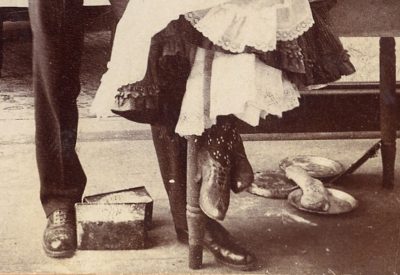

For more than 35 years, drawing on his skills as an imaginative illusionist, a workman-like tinkerer, and a worshiper of film frame-by-frame, Ken Jacobs has confronted reality and unmasked established powers. He creates, through his art, disorienting experiences which strangely empower the viewer. Combining elements of comedy, tragedy, history, and mystery, his artistry connects the viewers with their feelings, their visual faculties, and most importantly, their experiences. In Hanky Panky January 1902, Jacobs “animates” a turn-of-the-century stereoscopic photograph in order to inject life into a frozen moment of Victorian-era titillation. According to Jacobs, “This film marks the invention of human sexuality and as such figures as an important turning point in the course of human affairs.”

Nicky Hamlyn’s films, mostly silent and shot using a Bolex 16mm film camera, focus on the relationship between camera and place. All films incorporate various in-camera techniques such as lap dissolves, exposure variables, focus shifts, single-frame sequences and time-lapse photography that alter and expand our perception of common objects. William Rose wrote of Hamlyn’s Basket video:

“Characteristic of Nicky Hamlyn’s work, Basket is a transformative representation of an everyday object. A yellow clothes peg basket hanging on a washing line moves steadily in the wind, the permutations of its twists and turns being optically intensified by the low resolution camera it was recorded on.”

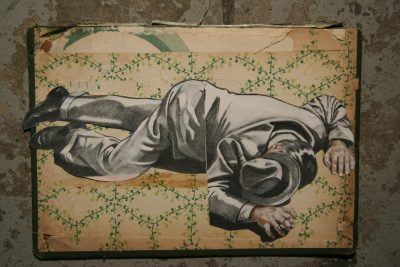

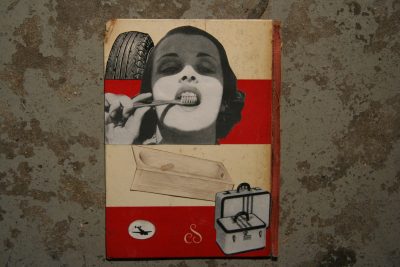

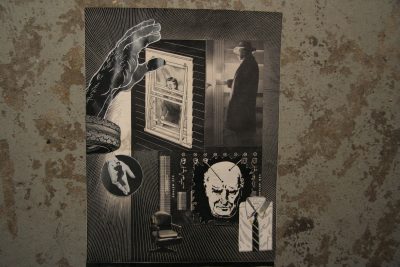

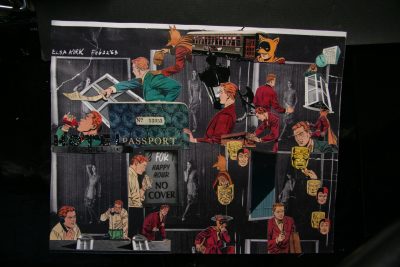

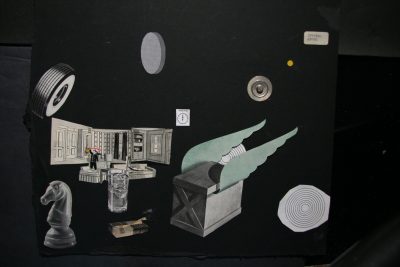

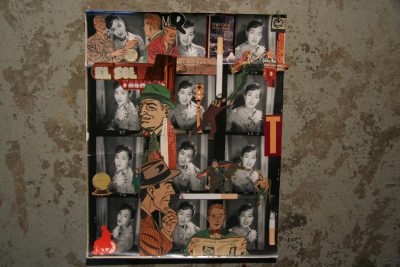

One of the most evocative, accessible, and culturally aware experimental filmmakers alive and working today, Lewis Klahr uses what we—and our parents—have discarded to tap into the 20th-century American spine. Locating a lost, damaged dreaminess in the magazine illustrations, product ads, furniture catalogs, comic books, and porn of the post-war era that define, whether we know it or not, our shared past, Klahr’s films construct archetypal narratives and mood trances out of the middle-class utopia we promised ourselves and never acquired. In Focus Pull, Klahr exhibits eight collage works from his animated films, works haunted by the ghosts of mid-century America, a place where Playboy chic meets film noir paranoia.

When Jorge Lorenzo’s handmade Pin Whole Series Application 1: Bulb is screened, the lens of the projector is off. It is a 16mm magnetic sound film-loop, pinholed frame-by-frame. Every pinhole is made in a different place within each frame in order to make a reading of the light coming from the bulb of the projector from a slightly different angle every time. Thus, the reflection of the bulb comes through the holes, producing the effect of animation. By putting pressure on the possibilities that the medium of film affords, this installation comments, experiments, and defies the reproducibility of film and its traditions of watching a recorded event on film by avoiding the film’s own viewing. In addition, the immediacy with which video is usually associated is here brought onto the medium of film, enabling it to portray images of the present rather than the past.

SUPPORT

Focus Pull: Onion City Off Screen is supported by the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts; the College of Architecture and the Arts, University of Illinois at Chicago; and a grant from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency.